I have been on the farm for two weeks, or about half my allotted time. Enough to make me feel like a veteran for my limited task load, but short enough to make me wish I would have more time here.

The days are long and hard. I find myself losing patience with the workload at the 12 hour mark. Of course, those 12 hours are punctuated with meal breaks. I remind myself that farming doesn't quit. It's a constant. You clean out a pen. And a few hours later, you clean out the same pen again. But somehow, it doesn't get boring to me. A friend told me "sometimes it's good to surface float". I agree. I'm surface floating and liking it. I don't have the capacity to go deep right now. I spent too many years in deep dives. It's time to discover the shallows.

I've had two days off. Both were anticipated with great excitement. On this last day off, I packed it in. I went for a facial at the wellness center of the very small town of Madison, checked out a used bookstore, did my laundry at the local laundromat, had a very southern lunch at a restaurant in Valdosta, GA, where I also managed to see Silver Linings Playbook. In my ordinary life, none of these things would be particularly exciting, or even appreciated. But on my one-day-off-the-farm in foreign territories, these activities were exciting, particularly my activities in Madison.

Wayne and Julia had to me that everyone knows everyone in Madison County (a dry county, BTW). And they weren't kidding. Madison proper is a small town located about 15 minutes from the farm. It has a historic downtown with walkable neighborhoods. Like most small towns, it has a post office. The main street has some businesses, but also like other main streets, it is clearly suffering. The pharmacy and hardware shops both closed down and the few remaining stores don't look particularly prosperous. I could not find a coffee shop.

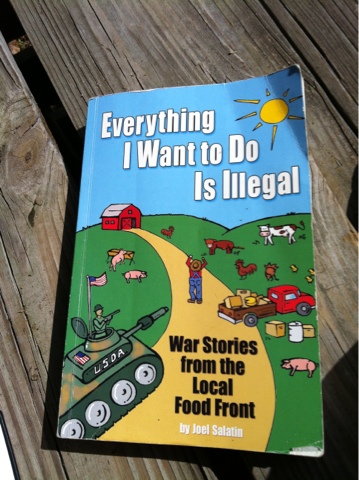

I was regarded with suspicion and highly noticed. Eyes followed my every move. It wasn't unfriendly, but I could see how it could be easily misinterpreted. The people were more wary than curious. As I snapped a picture of a main street building that is vacant and for sale, I was watched with rapt attention by a man driving a repair truck of some kind. I've been to my share of small towns. This one gets the prize for hyper alertness. The elderly lady in the bookstore almost blocked me from entering her store. I asked her, "Can I look around?" She was, I believe, more taken off balance by the fact that I was a bonafide customer than anything. I bought a book by Jimmy Carter entitled, "Our Endangered Values" and this seemed to relax her a bit. Particularly since the book I carried into the store was called "Everything I want to do is illegal" by the legendary farmer, Joel Salatin. She did ask me about the book, after all, she is clearly devoted to books. I give her credit for that. I explained to her that Joel is an organic farmer from Virginia. I have to admit the cover image with the USDA army tank aimed at him on his farm is a bit disconcerting. But that is Joel Salatin. Definitely an important voice of our times.

The scene in the laundromat was slightly more relaxed. It was not the nicest laundromat in terms of equipment, but the owner was around as was the repairman. People were more jolly and I was looked after. I befriended a young girl of about 3 years old. She went straight for the iPhone, and like other digital natives, was into my archives of videos within seconds. Every goat was a "dog". And chickens were regarded with high disdain.

Which basically sums it up for me as well.

Sunday, February 24, 2013

Sunday, February 17, 2013

Zen, chickens and 20 somethings

After a full week of farming, I'm deeply in the groove and finding myself loving it. In my previous life, my mind was extremely active, filled with ideas, worries, and idle obsessions. But here at Serenity Acres, I'm allowed to fully focus on the present and my work has a zen- like quality with hyper attention to detail. As a result, the mundane becomes pleasurable. I find myself thanking the hens for the eggs that I collect, conversing with the goats as I clean their pens, and valuing thoroughness over speed in all my tasks.

A typical day for me is a long day. I awaken at 6:40 am and begin my barnyard tasks by 7 am. The early morning routine consists of checking on the animals, feeding the animals, and cleaning their pens. Breakfast is around 9:30 am. After that, chores continue until noon. At 2 pm, we begin chores again and work continuously until about 6:15 pm. I usually help with the collection of the eggs, something I enjoy, because it resembles an Easter egg hunt. The chickens here are extreme free range and we find eggs in the pens, hay lofts, a random chair, and occasionally in the woods.

Of all the animals, I like the chickens least of all. But I am grateful for their eggs and have finally found the courage to reach my hand under the hens to take their loot. Chickens will lay only one egg per day, and when it is cold, they may only lay one egg every three days. For some incomprehensible reason, some nests are more productive than others. I found one bed with 9 eggs in it at a time. The processing of the eggs is time consuming. They have to be collected, soaked, washed, and candled, which means inspecting each one for imperfections such as blood clots, stains, cracks or oversized air pockets. Afterwards, each egg is weighed and placed into container according to their size. It is definitely not a money making proposition for the farm, at least without the help of the intern labor.

I'm slowly getting to know the other interns. Right now, we are all women, 5 of us, plus 2 women managers. One lucky guy, a former intern named Brock, joined us for a few days. Apparently, the ratios are constantly changing between male and female so I cannot make any observations about the future of farming. However, everyone is generally young, 20-something, and I and another intern, Lani, are the exception.

Lani is 57. Unlike me, she is married. Like me, she is empty nested. I asked her about her motivation to Wwoof and her reasons were pretty straight forward. As a New Englander, she wanted to escape the cold winters and had wearied of the winter vacations to the beaches. Like me, she shares an intense interest in food and farming and wanted to spend concentrated time in one place. She will be Wwoofing for 5 months at two different farms while her husband holds down the fort up north. Her husband, a bit older at 70, took it all in stride and was ok with it. Wwoofing is hard work and Lani does not shirk from her duties despite a physical condition that prevents her from really heavy lifting. I have found her to be an inspiration as well as a great teacher and guide in my initial days on the farm.

It's an interesting dynamic to be spending so much time with young people. In the evening, during our shared dinner meal, I find myself watching the younger interns and managers and feeling hopeful about our future as a country. With their adult lives fully ahead of them, with all the pressure of earning money and becoming established in the collective version of the American dream, these young people are making bold and radical choices. They are learning first hand how to produce and prepare food, care for animals, and live in community with little material possessions. Brock, for example, has been traveling for years. I asked him about his traveling. He hitchhikes, travels with a backpack and tent, and moves from farm to farm soaking up knowledge and meeting interesting people. In March, he will begin a paid internship with a farm in Sacramento. His dream is to have a farm someday, but he doesn't seem to be in a hurry, nor does he seem to be particularly goal focused or strident in any way. I would say that is true for everyone here. There seems to be a healthy balanced attitude about the future. There are dreams. And then there are eggs to be collected and pens to be cleaned.

A typical day for me is a long day. I awaken at 6:40 am and begin my barnyard tasks by 7 am. The early morning routine consists of checking on the animals, feeding the animals, and cleaning their pens. Breakfast is around 9:30 am. After that, chores continue until noon. At 2 pm, we begin chores again and work continuously until about 6:15 pm. I usually help with the collection of the eggs, something I enjoy, because it resembles an Easter egg hunt. The chickens here are extreme free range and we find eggs in the pens, hay lofts, a random chair, and occasionally in the woods.

Of all the animals, I like the chickens least of all. But I am grateful for their eggs and have finally found the courage to reach my hand under the hens to take their loot. Chickens will lay only one egg per day, and when it is cold, they may only lay one egg every three days. For some incomprehensible reason, some nests are more productive than others. I found one bed with 9 eggs in it at a time. The processing of the eggs is time consuming. They have to be collected, soaked, washed, and candled, which means inspecting each one for imperfections such as blood clots, stains, cracks or oversized air pockets. Afterwards, each egg is weighed and placed into container according to their size. It is definitely not a money making proposition for the farm, at least without the help of the intern labor.

I'm slowly getting to know the other interns. Right now, we are all women, 5 of us, plus 2 women managers. One lucky guy, a former intern named Brock, joined us for a few days. Apparently, the ratios are constantly changing between male and female so I cannot make any observations about the future of farming. However, everyone is generally young, 20-something, and I and another intern, Lani, are the exception.

Lani is 57. Unlike me, she is married. Like me, she is empty nested. I asked her about her motivation to Wwoof and her reasons were pretty straight forward. As a New Englander, she wanted to escape the cold winters and had wearied of the winter vacations to the beaches. Like me, she shares an intense interest in food and farming and wanted to spend concentrated time in one place. She will be Wwoofing for 5 months at two different farms while her husband holds down the fort up north. Her husband, a bit older at 70, took it all in stride and was ok with it. Wwoofing is hard work and Lani does not shirk from her duties despite a physical condition that prevents her from really heavy lifting. I have found her to be an inspiration as well as a great teacher and guide in my initial days on the farm.

It's an interesting dynamic to be spending so much time with young people. In the evening, during our shared dinner meal, I find myself watching the younger interns and managers and feeling hopeful about our future as a country. With their adult lives fully ahead of them, with all the pressure of earning money and becoming established in the collective version of the American dream, these young people are making bold and radical choices. They are learning first hand how to produce and prepare food, care for animals, and live in community with little material possessions. Brock, for example, has been traveling for years. I asked him about his traveling. He hitchhikes, travels with a backpack and tent, and moves from farm to farm soaking up knowledge and meeting interesting people. In March, he will begin a paid internship with a farm in Sacramento. His dream is to have a farm someday, but he doesn't seem to be in a hurry, nor does he seem to be particularly goal focused or strident in any way. I would say that is true for everyone here. There seems to be a healthy balanced attitude about the future. There are dreams. And then there are eggs to be collected and pens to be cleaned.

Tuesday, February 12, 2013

Endless exits all the same and connecting to my inner hick

I arrived at my first WWOOFING (world wide opportunities on organic farms.org) farm in northern Florida during unseasonably warm weather. I was surprised at how desolate northern Florida seemed to be. Once I turned off of I95, the views were mostly wooded and free of the cookie cutter exits that had populated my 13 plus hour drive down from Maryland. During the drive, I actually found myself wondering if it would be possible to drive across the country and never have a sense of place--to eat and sleep only in corporate chain businesses. I imagined someone from a foreign country coming here only to see endless exits of Country Kitchens, Kentucky Fried Chickens, and Quality Inns punctuating every 10 miles of roadway, never experiencing anything authentic. I decided that is is possible, and got a little depressed about it. Thus, Florida's I-10 was a happy relief.

The farm itself was a happy relief too. The drive from the interstate confirmed what I knew, I would be isolated-- dinners out would not be happening. Once I found the correct sandy road into the property, I was cheerfully greeted by chickens, dogs, and humans. The farm, Serenity Acres Goat and Dairy Farm, specializes in milk goats, but their love of animals clearly extends to many. There are 9 dogs, 2 cats, 3 horses, a noisy family of ducks, a few hundred chickens and more than 75 goats. While there is a small garden, animal husbandry is the thing. A full- time occupation and our complete focus.

Wayne and Julia, our fearless leaders, fell into goat farming because of their love of animals. After essentially rescuing nearly a dozen goats, they quickly found themselves farming and yielding more raw goat's milk than they could consume. They tried their hand at selling some "value added products" at the local farmer's market and had an overwhelming response. The farm has grown rapidly since then and they produce an impressive array of goat cheeses and soaps. The eggs are also extremely popular and are all pre- ordered, despite their pricey $4.50 per dozen.

Wayne was upfront about their small business: they are not yet making money and hope to be a year from now plus. I love that he was upfront about it (and not surprised), but I also think it serves a selfish purpose. We, the wwoofers, and 2 farm managers, are asked to work obscene hours--far more than the 25 hours per week wwoofers are traditionally asked to work. Knowing that we are contributing to a greater cause might help that fact go down. I personally am fine with the arrangement. I appreciate their clear commitment to excellence, obvious in every task execution, from first rate care of the animals, to compulsive attention to sanitation. But what impresses me most is their willingness to invest in their farm. The equipment, gates, fences, irrigation systems, kitchens, and pens are well designed and well maintained. While I am sure efficiency could be improved, I find myself pleased to be a cog in a well oiled machine.

Our accommodations are fairly deluxe as far as WWOOFING standards go. 6 of us share a 3 bedroom house, complete with a kitchen, 2 bathrooms, a fireplace, big screen TV, washer, and a large front porch, perfect for connecting to your inner hick. I have to admit that the house looks pretty scary from the outside, like a double-wide from a horror film, but inside its quite decent and tidy, and is far more comfortable than I ever expected.

The farm itself was a happy relief too. The drive from the interstate confirmed what I knew, I would be isolated-- dinners out would not be happening. Once I found the correct sandy road into the property, I was cheerfully greeted by chickens, dogs, and humans. The farm, Serenity Acres Goat and Dairy Farm, specializes in milk goats, but their love of animals clearly extends to many. There are 9 dogs, 2 cats, 3 horses, a noisy family of ducks, a few hundred chickens and more than 75 goats. While there is a small garden, animal husbandry is the thing. A full- time occupation and our complete focus.

Wayne and Julia, our fearless leaders, fell into goat farming because of their love of animals. After essentially rescuing nearly a dozen goats, they quickly found themselves farming and yielding more raw goat's milk than they could consume. They tried their hand at selling some "value added products" at the local farmer's market and had an overwhelming response. The farm has grown rapidly since then and they produce an impressive array of goat cheeses and soaps. The eggs are also extremely popular and are all pre- ordered, despite their pricey $4.50 per dozen.

Wayne was upfront about their small business: they are not yet making money and hope to be a year from now plus. I love that he was upfront about it (and not surprised), but I also think it serves a selfish purpose. We, the wwoofers, and 2 farm managers, are asked to work obscene hours--far more than the 25 hours per week wwoofers are traditionally asked to work. Knowing that we are contributing to a greater cause might help that fact go down. I personally am fine with the arrangement. I appreciate their clear commitment to excellence, obvious in every task execution, from first rate care of the animals, to compulsive attention to sanitation. But what impresses me most is their willingness to invest in their farm. The equipment, gates, fences, irrigation systems, kitchens, and pens are well designed and well maintained. While I am sure efficiency could be improved, I find myself pleased to be a cog in a well oiled machine.

Our accommodations are fairly deluxe as far as WWOOFING standards go. 6 of us share a 3 bedroom house, complete with a kitchen, 2 bathrooms, a fireplace, big screen TV, washer, and a large front porch, perfect for connecting to your inner hick. I have to admit that the house looks pretty scary from the outside, like a double-wide from a horror film, but inside its quite decent and tidy, and is far more comfortable than I ever expected.

Sunday, February 3, 2013

Beaches, addictions and Poverty of the Soul

Our final week in Peru was spent in the North, in a town called Mancora. Mancora is a couple hundred kilometers from Ecuador and probably about 500 kilometers from the equator. Thanks to a strong breeze, we were able to stay cool in the shade, but when we were in the sun, it was brutally hot. And despite our efforts to stay in the shade, we both got burned and browned in equal measures.

The ocean was fierce, with high waves most of the time--great for the surfers, but rough for swimming. We were able to find a swimming hole behind some rocks not far from our hotel. I loved watching the children, all Peruvians on vacation, swimming in the shallows and playing in the shadows of the rocks while the waves crashed over them. When the waves roared in, I could see hundreds of tiny sand crabs burrowing into the sand. It reminded me of my younger days in Ocean City, when we would catch the larger version of these crabs in our sand buckets. In later years, I stopped seeing the sand crabs and I assumed that they were a victim of deteriorating water quality.

Getting to and from town turned out to be an adventure in itself. We had to take "motor taxis" along a dusty road. The drivers ranged from middle aged and portly (would we make it up the hill?) to young and macho (will we survive this?) and one night Barbara and I couldn't stop laughing and screaming as our driver careened around corners and flew over bumps while we held on with all our strength.

Even in a beach town, the upstanding character of the Peruvians has remained. I have been struck by all the things that I haven't seen since I've been in Peru: I've never seen anyone drunk or on drugs, I've never seen anyone arguing or fighting, I've never seen a child hit or yelled at, and I've seen very little littering (even in Lima, a city of 10 million people). Children are everywhere, integrated into every aspect of daily life, in markets, restaurants, plazas, and shops.

Even in these final days, I can honestly say that my original impression of "Peruvians are peace" has held up. In fact, I would have to say that I've never been in the presence of more consistently kind, low key, unflappable people in my life.

It is hard not to compare life here to life in the United States. And I would be the first to admit that I should not idealize Peru. But there are some key things that stand out. For one, the family unit is extremely strong here. Extended families gather together for meals and entertainment on the weekends. It is common for multi generations to live together, and elders are highly respected. There are no social programs--no unemployment insurance, welfare, and the health system is not strong, but it does exist. Yet, there is also no homelessness. There is hunger and malnutrition, but people are not starving. It is possible to get a good education, but it is less likely to occur in the rural areas. And extreme poverty does exist.

What I don't see is the poverty of the soul that exists in the US. This is a strong statement. And I do not make it lightly. But this is a culture that is not fueled by fear, nor is it driven by material possessions, status or shaped by violence--all characteristics of my own culture. So it is intriguing to me that it also is a culture where depression, addictions and homelessness are almost nonexistent.

Being from Baltimore, a city that inspired The Wire, and having had devoted my career to community development, I am fascinated, if not frightened by the trajectory of my own culture. And even with my best intentions, I too got off track. I would not be seeking peace in Peru if that were not the case.

The ocean was fierce, with high waves most of the time--great for the surfers, but rough for swimming. We were able to find a swimming hole behind some rocks not far from our hotel. I loved watching the children, all Peruvians on vacation, swimming in the shallows and playing in the shadows of the rocks while the waves crashed over them. When the waves roared in, I could see hundreds of tiny sand crabs burrowing into the sand. It reminded me of my younger days in Ocean City, when we would catch the larger version of these crabs in our sand buckets. In later years, I stopped seeing the sand crabs and I assumed that they were a victim of deteriorating water quality.

Getting to and from town turned out to be an adventure in itself. We had to take "motor taxis" along a dusty road. The drivers ranged from middle aged and portly (would we make it up the hill?) to young and macho (will we survive this?) and one night Barbara and I couldn't stop laughing and screaming as our driver careened around corners and flew over bumps while we held on with all our strength.

Even in a beach town, the upstanding character of the Peruvians has remained. I have been struck by all the things that I haven't seen since I've been in Peru: I've never seen anyone drunk or on drugs, I've never seen anyone arguing or fighting, I've never seen a child hit or yelled at, and I've seen very little littering (even in Lima, a city of 10 million people). Children are everywhere, integrated into every aspect of daily life, in markets, restaurants, plazas, and shops.

Even in these final days, I can honestly say that my original impression of "Peruvians are peace" has held up. In fact, I would have to say that I've never been in the presence of more consistently kind, low key, unflappable people in my life.

It is hard not to compare life here to life in the United States. And I would be the first to admit that I should not idealize Peru. But there are some key things that stand out. For one, the family unit is extremely strong here. Extended families gather together for meals and entertainment on the weekends. It is common for multi generations to live together, and elders are highly respected. There are no social programs--no unemployment insurance, welfare, and the health system is not strong, but it does exist. Yet, there is also no homelessness. There is hunger and malnutrition, but people are not starving. It is possible to get a good education, but it is less likely to occur in the rural areas. And extreme poverty does exist.

What I don't see is the poverty of the soul that exists in the US. This is a strong statement. And I do not make it lightly. But this is a culture that is not fueled by fear, nor is it driven by material possessions, status or shaped by violence--all characteristics of my own culture. So it is intriguing to me that it also is a culture where depression, addictions and homelessness are almost nonexistent.

Being from Baltimore, a city that inspired The Wire, and having had devoted my career to community development, I am fascinated, if not frightened by the trajectory of my own culture. And even with my best intentions, I too got off track. I would not be seeking peace in Peru if that were not the case.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)